I’ve got a confession to make. When I got the initial phone call from Ascend Books to collaborate with Marian E. Washington on her autobiography, I knew almost nothing about her. I could have told you she was a longtime coach of women’s basketball at the University of Kansas.

I thought I had a good handle on women’s basketball history, particularly given my years covering Old Dominion. I knew the stories behind Nancy, Inge, Anne and Marianne Stanley. I chronicled the impact of Wendy Larry and Ticha Penicheiro.

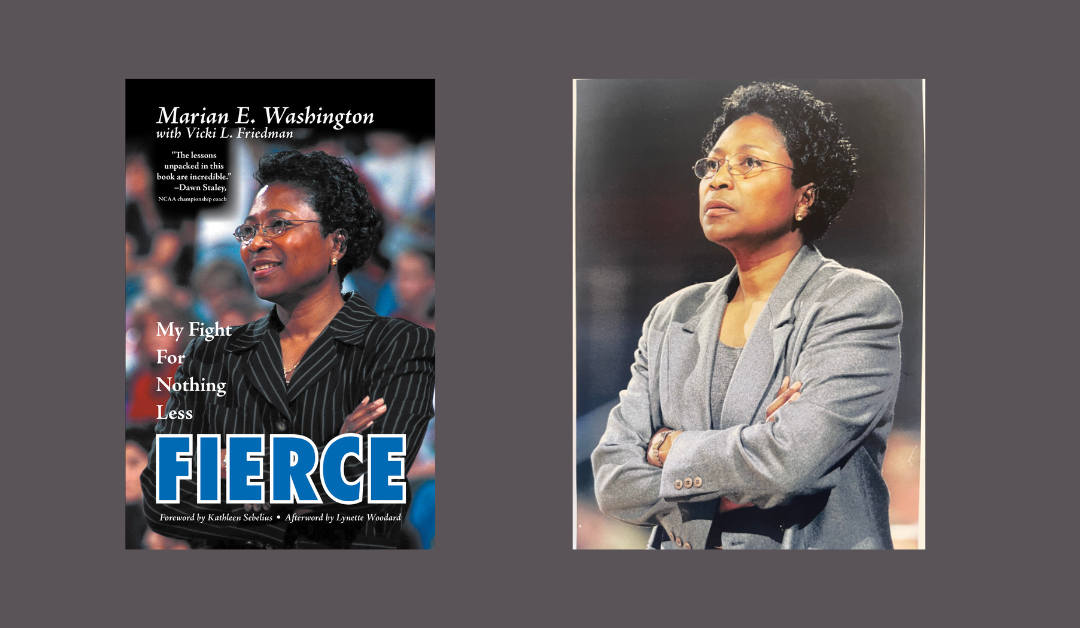

What I discovered in spending more than a year working with Marian on “FIERCE: My Fight for Nothing Less,” which will be released on Aug. 6, was how little I really knew.

I could have told you what the initials NCAA and AIAW stood for, but I had never heard of the CIAW. Marian’s college coach at West Chester State (today West Chester University) was Carol Eckman. She organized the first-ever national championship under the CIAW by inviting 16 of the top women’s collegiate teams in the country to a tournament. Marian was one of two African American players on that inaugural championship team in 1969. The entire time she was in school, Marian worked a full-time job – at night.

Marian didn’t benefit from being surrounded by a team of coaches yet she found a way to excel as an athlete. Three times she reached the Olympic Trials for track and field despite having no formal instruction in throwing. She was even closer to the Olympics as a basketball player, part of the 1972 USA national team that, due to an oversight, was unable to compete despite years of training. The 1976 U.S. national team is inducted into the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame. But what came before has been forgotten, overlooked twice you might say.

Marian’s hire at Kansas was groundbreaking and twofold. In 2022, The Washington Post recognized the Jackie Robinsons of 20 sports – trailblazers who broke the color barrier just as he did in baseball. Marian was named the Jackie Robinson of women’s basketball coaching, the first African American woman to coach at a Division I level at a predominantly white institution, hired by the University of Kansas in 1973. A year later, with universities recognizing they needed to comply with newly passed Title IX legislation, Marian was appointed director of women’s intercollegiate athletics at Kansas.

I want you to picture that. A Black woman in a leadership role of an athletics department of a Midwestern school in 1974. It was a bold hire by Kansas. It was a daunting mission for Marian, given a meager budget to work with. Women had nothing in KU’s Allen Fieldhouse prior to her arrival. Imagine holding your pre-game and postgame inside of the public women’s restroom. There was no pre-game meal. There were no uniforms to call your own. There were no showers available after games. Coaches had to be hired. Schedules had to be created. Marian had to find space, build offices – literally have walls built for offices. When other schools began awarding women athletic scholarships, she had to find a way to do the same at Kansas.

Marian laid the foundation for what is today one of the finest academic programs in the nation. She did it while coaching basketball. She did it while coaching track and field – a program she founded in 1974. She did it while raising a daughter. And yes, she did it despite the resistance of several who didn’t want her to succeed. That is part of her legacy in addition to the 560 victories she amassed as a coach for 31 years.

Yet her impact goes beyond that. As late at the ’90s, Marian was disappointed in USA Basketball for not hiring minority coaches on their staffs. No assistant coaches were Black and certainly no head coaches. She worked tirelessly to change that and in 1996 became the first Black woman on an Olympic coaching staff as an assistant to Tara VanDerveer for the start of a gold medal run that will likely continue today under Cheryl Reeve.

“We have a tendency to forget where thing started and who opened doors for us,” said Dawn Staley, the three-time national championship coach at South Carolina and Naismith Hall-of-Famer.

Marian opened the door for Dawn Staley.

Marian was fierce in her fight for equity and equality. She never got sidetracked on the mission of giving female athletes what they deserved. She wasn’t asking for women to receive special privileges. But she wouldn’t settle for something lesser, either.

Coaches, I encourage you to read Marian’s book. I hope it will inspire you, and I know it will educate you and your players about a largely forgotten history told in the words of someone who was there. Someone, as Staley said, “who gives us a glimpse of what greatness looks like, what a legacy looks like, that tells us what we don’t know but need to know.”

FIERCE: My Fight for Nothing Less is available on Amazon.